Description

This two volume work is a pioneering effort by a stalwart of Indian Philosophy in German Language. Since this provides new insights, largely uncovered by other authors of Indian Philosophy, hence there was great demand and need for publishing this English translation.

In the composition of this work the three fold aim is—I. Presentation of Indian Philosophy from the beginnings to the present times in which every phenomenon of importance finds its corresponding place. II. To present the reader a real history of Indian Philosophy, not a crude assemblage of half-worked materials but as far as it is possible a description of the origin of single doctrines and systems and of their development which should be beyond the accidentally of traditions. III. Finally, an attempt is made to give the work a readable form. It should not bring in scientific discussions but a presentation of the results of scientific research.

The first part, the first volume of which appears herewith, is devoted to the oldest period of Indian Philosophy from the beginnings until towards the end of the first millennium after Christ. The first volume embraces the earliest period and the Samkhya and the Yoga systems arid therefore, already thus goes beyond the detailed volume of Deussen’s presentation. The following volumes set forth the presentation of the nature- philosophical systems, above all the Vaigesika, the Buddhistic systems and the period of the second blossoming, which in the sphere of Epistemology and Logic, performed the most important achievements. The second Part will embrace the philosophy of the later times and will carry the presentation up to the present times.

Erich Frauwallner was born in 1898 in Vienna and was admitted in 1928 as University lecturer for Indian Philology and Ancient Cultural Sciences. From 1939 to 1945, he was Professor of Indology and Iranistik, Since 1945, when the Faculty in the University was closed, he lived as private Professor in Vienna.

There is a knowledge which does not aim at a particular object or a limited sphere of objects but which concentrates itself on the Unity of the Objects, on their connection. The thought directed on this unity must at last step beyond the objects and their empirical isolated relations and must transcend them in order to gain the horizon through which the Whole comes into view. This coming into view of the Whole is, however, the essence of the theory. The history of human thought, in philosophy as well as in science, shows that the thought has this relation to the Whole, that it is continually sustained in the direction of the unity and the total comprehension of the Knowable Whole. Whether the Whole of Reality can be comprehensible objectively in a definite collection of Knowledge is a different question perhaps this remains no question for him who thinks that the Whole (inclusive) of the objects can again never be itself an object among others.

But when the whole as an object is never attainable on the objective level but is a truth which the thought will never be able to grasp, then another way must be trodden. The objects are not the objects of this goal which leads to something beyond them in the transcending movement of thought that leads to the Whole of existence beyond the objects. This way has also the starting point, the end-point or the goal, with the direction. The end-point or the goal is the whole; the starting-point, starting from which the direction sets itself towards the whole, is the point from which the thought must start, in order to be able to reach generally the Whole ; it is the ground and for the widest, most comprehensive Whole, it is the last ground or the ‘Ur-ground.’

Only from the highest peak of a mountain, there opens the view on the whole of the landscape. The ground or foundation of a building must be all the more deeply laid, if the building is bigger. The building which should embrace the Whole world must have the deepest foundation. Out of the root which seizes the deepest in the earth, the tree raises itself to the developed form and fullness. As these images of the mountain, the building and the tree make a graphic impression, so do the ground (basis) and the whole stand related and ordered with one another. There is no whole without the ground and without the whole the ground is no ground. The structure of thought, which can unlock the reality, forms the arrangement or ordering of the ground and the whole. in respect of this problem of the ground, Logic must be taken note of: The thought strives not only to know a definite object i.e. to define what it is (idea, definition) and to ascertain that in fact it is (judgment) but to prove, why it is. The integrity of the stated logical structure of thought which defines from the point of ideas, which judges and proves, is, however, disturbed if these forms of symbolization of thinking and representative presentation are mixed with one another. The thought which defines an object, the defining, limiting thought cannot be, in one stroke, equated with the thought that proves out of this is produced a logical deformation with all its consequences. Thus the structurally logical distinction between the thought of the ground and of the objects is an important start for the understanding of the theoretical thought form which mediates between the ground and the object.

The series of grounds must be carried up to the last in order to be able to fulfil their function of proof. It is not accidental that everywhere, where the whole of existence or the world comes into the view-point of an all-embracing thought, a question is at the same time raised regarding the ultimate ground or cause, or regarding the ground of the world. The world as an all-embracing unity is, in general, to be perceived only from the ultimate ground. Tins ultimate ground being the last and the ultimate one is no more to be proved, it is unconditioned, why, in its basis it is the unconditioned itself the Absolute. Thus are seen the Ground and the Whole—the absolute Ground and the all-embracing Whole which we call as the world, attuned with one another, ordered in relation to one another into a connection in which the thought attains its full, integral form- dimension. From the Absolute as (ultimate) ground, the whole of the existing as the world is and must be always taken into consideration. Because one must be clear about the fact that this most basic thought in the ultimate sense gives the historical and principal basis for all the systematic fundamental thoroughness of thought to which claim is laid in philosophy as well as in science.

It is an occurrence from the point of world-history that this thought has first made its structure evident in the books of the wisdom of ancient India, that there it first unfolded itself, and underwent its first historical formulation. Therein lies the importance of ancient Indian thought, “these earliest impulses of philosophical thought, of which we know” (G. Misch), as the historical beginning of philosophy.

It cannot be disputed that the innermost unity and the ultimate ground (cause) of the world forms the theme of the oldest Indian speculation. It is a fact that this speculation has originated with religion in the closest connection with it and has unfolded itself out of its connection with the Absolute. One could assert about every philosophy that it is obliged to religion for its origin in the epochal sense. Still this relation shows a characteristic difference. The Greek Philosophy is related to religion dialectically and develops itself out of contrast to it, in the form of that other religion of thought, purified through reason, formed in the form of the concept which has brought forth the philosophical God- idea, independent of religion in the idea of the good (Plato) and of the unmoved mover (Aristotle). Such is not the case with Indian thought. The Indian speculation has never departed from the soil or field of religion ; it rather nourishes itself continually and directly out of the forces of this soil (of religion) from which it never uprooted itself. The speculation has, however, from its side reformed and developed the structure of religion from the inside. And thus the process was introduced which led from polytheism, the doctrine of many godheads and henotheism, through the favouring of one god, to Pantheism so characteristic of Indians, the unity of God aid the world. This process was started— and therein consists its agreement with the Greek Philosophy through the metaphysical, theoretical thought-form, through that thinking which, detaching itself from the empirical manifoldness. strives in such absoluteness after radical unification, after the unity from the root itself, after the unity arising out 0f the ultimate root, after an absolute unity of manifold things out of an ultimate ground or Ur-ground. When this thought starts, all multifariousness, all the manifoldness of the external world goes into the mill of the last doubting and deactivation. This empirical world is, in its compact immanence as the world, shaken up through the questionability of its variegated manifoldness, of the abundance of its form and look which overpower the naive mind of the sensuous or the materialistic. Now the mind wishes to withdraw itself from the power of the abundance and gain for itself a form of the world, not out of the sensuous, but out of the mind. The reflecting mind succeeds in overcoming the sensuous manifold through a significant unity and in allowing to understand out of it a meaningful and therefore an understandable whole, as the world only in general.

This process of crisis seizes the world of the senses, of the sensuous experience in its whole extension, and therefore also the graphic forms of the gods of the polytheistic religion. When God India, in a song3, as one intoxicated with the Soma-drink is derided as a reeling drunkard, the godliness itself totters in its appearance and vanishes with it. This deep-reaching crisis of religious consciousness from which the most shining figure of the divine world, like India himself,—the remaining are seen ridiculed in a song us frogs4—does not remain spared, can only be explained through the breaking-in of a new, world-building thought which is able to—and wishes to—abstract itself from the several individual gods5. This thought breaks its old path through the twilight of the gods which was generated by it, and brings forth the sun of a new god which, with its light, still illuminates the sunken forms of the past. That it is, as a matter of fact, the philosophical, metaphysical thought of unity which here breaks forth, may be proved in isolated particular cases.

The four collections of the Veda (Rg-, Sama-, Yajur, and Atharva-veda-) contain as their inner kernel the songs and the prayers of sacrificial liturgy in religious poetry. Around this kernel, there are joined, following one another, like shells, the Brähmana works for the interpretation of the ritual and sacrificial ceremonies, the Aranyakas or forest books, embodying the thoughts, arising among the thinkers in the loneliness of the forest, and the Upaniads, containing the reflections arising out of meditative absorption in the Brahma, the holiest of all. Thus one can read into them a sequence of steps which leads, from the religious experiences and revelations of the poet and the seer of the past ages on the way of reflection and meditation, to making accessible the kernel of the Brahma itself, as in the Upaniads, through a meditative thought-process which stands out as essentially different from the Western Logic of ideas and dialectic. This process of the conviction of the transcending experiences in the thought-form of its available presentation is, at bottom, the process of the theory in which the Indian thought, in spite of the above-mentioned distinctive thought-structures, is connected with the Western thought. It is, therefore, well justified to lay, at the basis, the movement of thought, meditative-thoughtful formulation of the contents of the experience or knowledge, as the basic process for all the formulations of ideas in Indian speculation.

It is indispensable, for right understanding, to comprehend the start of this metaphysical-theoretical thought-movement rightly. While doing so, one should take into consideration that the meditative thought of the original texts arises out of religious poetry, from the songs and the prayers which belong to the constituents of sacrificial liturgy. This liturgy is holy service and consists as such, in the realization of a transcendent, holy order in the world, that order (i-tam) according to which the sacrifice is to be performed. The songs and the prayers accompany the sacrificial performance and embody in their wording its full significance. The words of the ritual text have the magical power to procure and bring forth the holy and the whole order of the world out of the holy, divine, Absolute itself wherein the wholeness of the world as the safe, intact whole of existence is secured out of the ultimate, transcendent ground, out of the Ur-ground. This essential identity of the ritual order with the absolute world-order, the essential character of its consummation for the maintenance and security of the order of the world, is the deepest significance of the ritual-cultic function. To produce again and again the holiness and the wholeness of the whole world and to maintain it securely, is the maintenance of the truth of the cultic performance; it has the world before its eyes, a continual perfection of the intact wholeness which arises out of the connection with the Absolute, this maintenance, this cultivation of the cult, a continual construction and building of the world being carried out on the ultimate, absolute ground, wherein culture according to the name and the fact stands ultimate and the deepest.

So it can be no wonder that the meditative reflection would be able to awaken the meaning and picture of the world out of this cultic ground. The holy cult-event revolving round the one centre, around the Absolute, allows the universe to arise spiritually before the contemplative vision. This universe is the original occurrence of world-formation and the foundation of the world as the all related to the unity, out of the ultimate ground. This is the original idea of the Universe arising out of the religious-cultic thought. The meditative reflection of artificial world-formation leads over or beyond the contents of the revelation of religious poetry, in an elucidating, clear and perspicuous way, to the structure of unity, to the close compactness, and the connection of the one ‘which the world in its innermost core holds together’ and gives rise to the reflecting thought with its own independent sharpness. It is a necessary consequence that, with the reflecting-meditative thought joined with the contents of knowledge or experiences of religious consciousness, there sets in a movement of thought which strives after the absolute point of unity of the world and allows all existing things to he included in the Absolute Unity as existing alone. This movement emerges forth in the hymn of unity of l)irghatamas6 in which, together with the removal of the gods, the one God, standing supreme over the gods or better still, the one Godhead, springs forth, first as the one, Prajapati, still thought of as a person, in order to present, however, later on, the (only) one, through more intensive formulation of meditative-abstractive thought in this beginning philosophical speculation. On account of this, this whole train of thought proves to be an original philosophical one and no more as a religious one, for which the concrete personalization of the ultimate ground of the world is always the song of unity (Rgveda 1. l64) culminates in the utterance : ekam sad vipra bahudha vandanti ‘the poets call, what is only one, many’.’ With this, it is clear that many gods are traced back by the religious poetry to one Godhead. The one (ekam) is not meant adjectively as a quality but as a substantive, as the upholding centre of reality. That is why it is said:tad ekam, the or that One. This One is at the same time everything, as it is emphasized in the Valakhilya hymn ekam vaidam bahudha sarvam This is one and has become all’. That is only possible through the fact that one has become wholly like a lump of salt9 which dissolves itself completely in the water of the sea and still remains contained therein. Therein becomes evident the limitless process of arising and passing away, ‘the rolling wheel’ (Nietzsche) of innumerable ups and downs, the godly process of natura naturans which brings forth everything and at the same time remains withdrawing into itself everything. The nature of the becoming (origin) lies in the beginning in which everything in the course (of development) is decided up- to the end which is already set forth jointly in the beginning. It is a difficult problem to unite or reconcile this end, which already lies in the world and in the immanence, with the beginning which must lie in the transcendent, in order to secure the permanent cycle of being. The decisive beginning which contains everything in itself and allows everything to depart out of itself, is the Origin. So the Origin must necessarily be the one which holds everything in itself in a simple form and this One as the creative reality must necessarily be the Origin leading to the unfoldment of the whole. The hymn of creation’° thus emphasizes that which lies at the basis of all objects and their distinctions, the absolute occurrence of the origin as the creative impulse of the unity: “Not the non-being (asad) ,nor also the being (sad), neither the death was at that time nor the life, neither the night nor the dazzling light of the day.” Thus the contrasts consisting of the dialectical texture of reality, until the last Ur-contrast of existence and non-existence, are overhauled in favour of the strong unity, the monology of the beginning.

| Introduction Into Indian Thought | XI | |

| Foreword of The Author | XLVII | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| 1 | The Periods of Indian Philosophy | 3 |

| 2 | The Tradition | 19 |

| I | The Philosophy Of The Ancient Period | 25 |

| A. The Angient Period | ||

| 3 | The Philosophy of The Veda | 27 |

| 4 | The Philosophy of The Epic The Yoga | 76 |

| 5 | The Buddha and The Jina | 117 |

| B. The Periods of The Systems | 215 | |

| 6 | The Samkhya And The Classical Yoga System | 217 |

| Bibliography (select) and Notes | ||

| Index | 355 | |

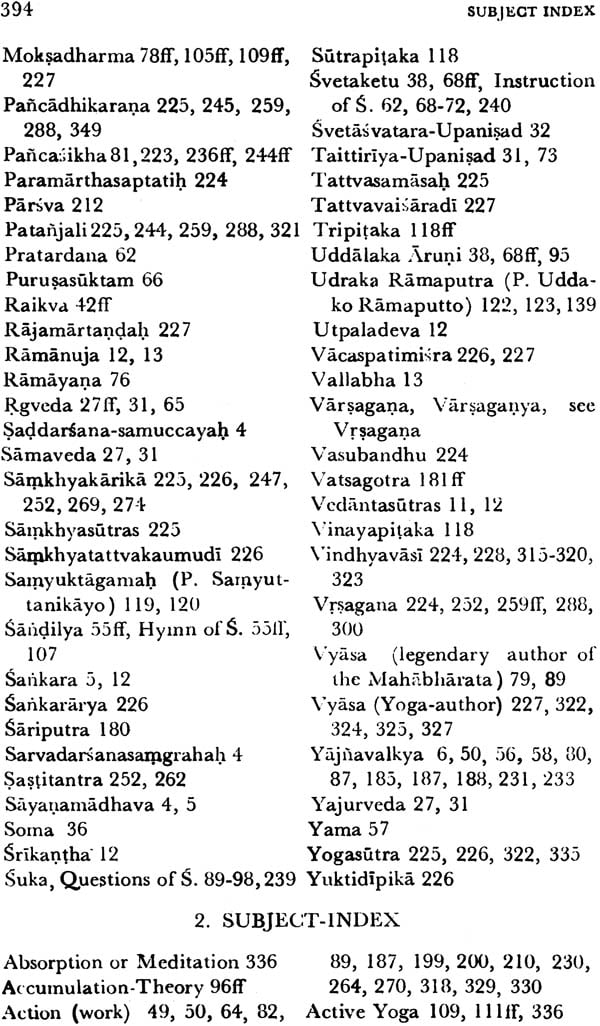

| 1 | Index of Names | 393 |

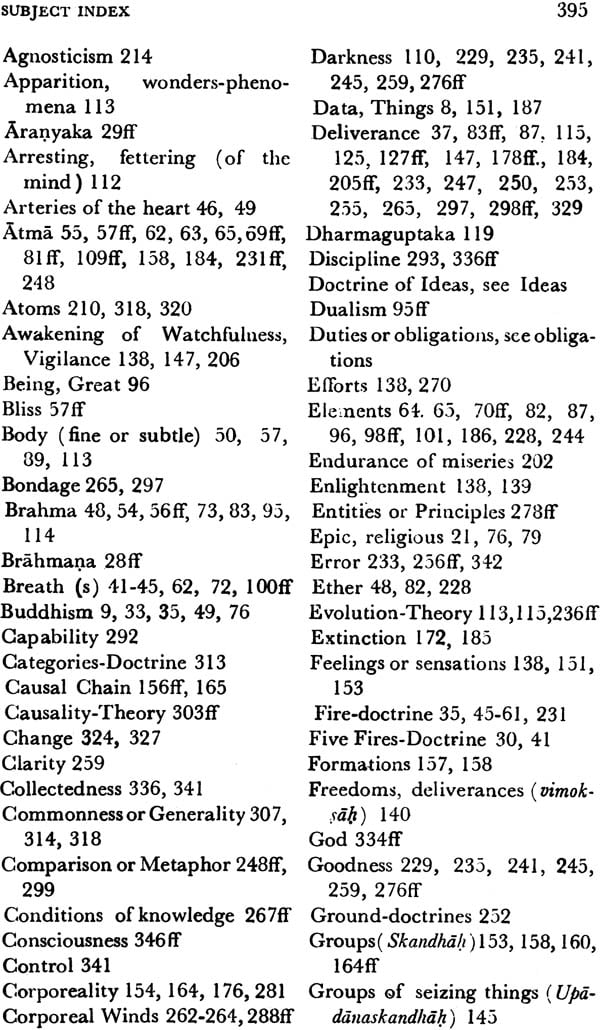

| 2 | Index of Subjects | 394 |

| 3 | Index of Indian Technical Terms | 298 |

| Foreword | VII | |

| B. The Period of The Systems (Continued) | ||

| 7 | The Nature-Philosophical Schools and The Vaisesika Systems | 3 |

| 8 | The Systems of The Jaina | 181 |

| 9 | The Materialism | 215 |

| Supplement | ||

| 1 | Select Bibliography and Notes | 229 |

| 2 | Index | 260 |

| 3 | Errata | 265 |

Sample Pages

Vol 1

Vol 2